In the summer of 2006, in Dubrovnik, the “smallest knot of the largest cravat” was tied – an act that marked the conclusion of a project symbolically connecting Croatian regions, their geographic and cultural diversity, under the title Cravat Around Croatia. However, the project – which American network CBS dubbed “the largest artwork in the world” – did more than highlight Croatia’s identity and present it as the “homeland of the cravat”; it also sought to establish a sense of closeness with the peoples of neighboring countries.

The decision to begin and end the two-month performance – based on the idea of Marijan Bušić and carried out by the non-profit institution Academia Cravatica – in Dubrovnik was grounded in several significant moments. The analogy of the knot as the key point, placed in the most important location, is justified; viewed through the lens of historical diachrony, Dubrovnik stands apart from other Croatian cities. It is no coincidence that during the 19th century, the Illyrians – leaders of the national revival – called it the “Athens of Croatia,” the “Illyrian Parnassus.” Indeed, in many respects Dubrovnik leads not only within Croatia, but on the global stage: the first quarantine was established here in 1377; it was the first to abolish slavery in 1416; and its maritime insurance law from 1568 is the oldest such law in the world.

But above all, Dubrovnik is unparalleled in defending its own values and identity. Above the entrance to Fort Lovrijenac is carved the inscription: “Freedom is not to be sold for all the treasures of the world.” The verses of Gundulić – “O beautiful, o dear, o sweet Liberty, gift in which all treasures are given by God above” – are known by every schoolchild. The importance of community embodied in the Republic, and the freedom it guaranteed, stood above all other values. Yet, Dubrovnik was never closed off or self-sufficient – it was always, as a “ruler of the sea,” deeply connected to the world.

Even in modesty, at least during its era of independence, Dubrovnik was a champion. Dubrovnik’s citizens never indulged in extravagance. It is well known that their meals were apostolically simple, unlike the elaborate dishes that filled the Renaissance tables of wealthy nations. By the standards of wealth, Dubrovnik could have taken part in opulence – but no! That would be boasting, a sin of pride. And just as they refrained from culinary excess, so too with clothing: compared to contemporary fashion, Dubrovnik attire is marked by simplicity, modest decoration, and a complete absence of extravagance. Looking from a modern perspective, we might say that the old Dubrovnikers embraced economy, aesthetics, and ethics – “less is more.”

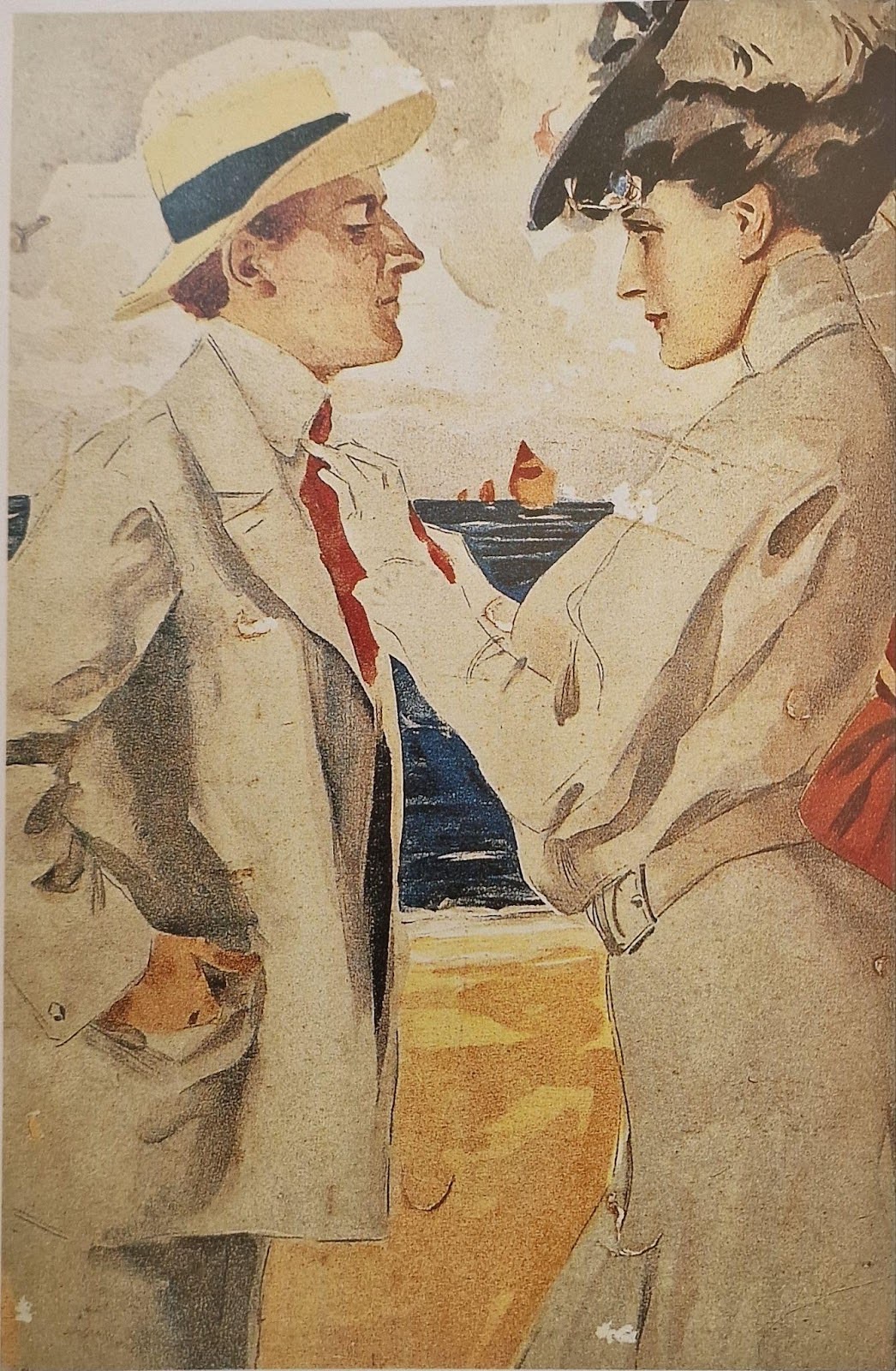

If we pause here to consider clothing specifically, we’ll note that the stiff collars with numerous folds, requiring large amounts of fabric – common in Western Europe during the late Middle Ages and Renaissance — are absent in Dubrovnik. Instead, we find something that could be interpreted as a precursor to the cravat. There are concrete examples as well. It is especially intriguing that in the portrait of Ivan Gundulić, the greatest Croatian Baroque poet, we see a long scarf (we could call it a neckerchief or shawl) wrapped around his neck. Even more striking is the identical item visible in the portrait of Ilija Crijević, a Dubrovnik humanist who lived until 1520, during the Renaissance. These are undoubtedly elements that call for further research and understanding of the topic, and the early recognition by Academia Cravatica of these previously overlooked details – the “prehistory of the cravat,” before it gained its globally known name – has already sparked great interest.

The story of Gundulić, whose 1622 portrait is kept in the Rector’s Palace, along with several other notable figures from Dubrovnik’s history connected to the cravat (and to figures from other countries, such as Vlaho Bukovac and Samson Fox, or Frano Supilo and Tomáš Masaryk), is shared with every visitor to Dubrovnik at the Museum Concept Store – the integrated museum section of the Croata Salon.

The strong presence of scarves in the folk costumes of many Croatian regions has also been documented in the territory of the Dubrovnik Republic in the mid-19th century. In places like Orebić and Janjina on the Pelješac peninsula, men tie scarves around their necks, while in Konavle and the Dubrovnik Littoral, scarves are worn only by women. Even during kolendavanje – a vibrant ancient tradition kept alive each year before Christmas – scarves and cravats are customarily worn.

Even the very symbolism of the cravat – a combination of obligation, represented by the knot, and freedom, expressed by the untied vertical end – is enough to permanently associate it with the Republic’s strict and just laws and with the City that so cherishes Libertas that it has adopted it as a slogan and emblazoned it on its flag. Should the project come to fruition whereby a cravat would encircle the city walls and extend toward the open sea, this realization of global visibility would leave a lasting mark of identity – strengthened further by the historically grounded presence of the cravat in the Dubrovnik region.